The Ins and Outs of Piano Tuning

This article focuses on the specifics of how to tune a piano for the purposes of enlightening piano owners. We will discuss several of the main considerations that must be addressed in tuning a piano properly, as well as some major pitfalls. While few people would assume tuning a piano is easy, it’s unlikely the lay person realizes just how many factors are involved in getting the job done right.

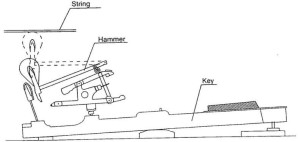

First, let’s just present an extremely general description of the tuning process. A piano has approximately 230 strings, give or take. Each string has a tuning peg attached to it which controls how tight it is. The tightness of the string, among other factors, controls its pitch. The piano tuner, using his ear or a tuning device, pulls each pin using a tuning hammer to make it looser or tighter until the string produces the correct pitch. Sounds pretty simple, right? If it were, piano owners would be tuning their pianos themselves.

One of the first issues that must be addressed is that there is no one standard by which all pianos are tuned. This is not because a standard has not been created. It’s because all pianos vibrate differently, and what sounds harmonious on one piano will be terribly discordant on another. Let’s attempt to understand why. A vibrating string carries many different vibrations known as harmonics. In theory, these harmonics are whole number multiples of the lowest vibration called the fundamental. If the main body of the string was vibrating 100 times per second, then portions of the string should also be vibrating at 200 times per second, 300 times per second, etc. In reality, this only works for strings that are perfectly flexible, which real strings are not. In the real world, the stiffer the string is, the less perfect the harmonics are. A real string might produce frequencies of 100hz, 201hz, 302hz, or something like that. The higher you go up the series, the more distortion there is. This distortion is called inharmonicity.

What does this mean when we tune a piano? It means that if you were to tune an octave perfectly, it would sound out of tune. The reason it would sound out of tune is that the harmonics of the lower note, due to their inharmonicity, would not line up with the harmonics of the upper note. To make an octave sound like its in tune, we have to tune the upper note a little higher than normal to get the harmonics to agree with the note below it.

Every piano has a different amount of inharmonicity. The shorter a piano is, the more problematic it is. The longer the piano is, the less problematic it is. The logic is simple. A longer string can flex more easily. On a spinet piano, which is the shortest type of piano you can buy, the highest note has to be tuned a whopping fifty cents higher than its predicted value to sound in tune. One cent is equivalent to one percent of one note, which means a C which is fifty cents sharp is actually halfway between a C and a C#. On a grand, one might only have to tune the highest note twenty cents sharp, due to the longer strings.

This is the first and probably most fundamental factor that must be addressed by any skilled tuner. Another very challenging issue is what we call setting the pin. The pins that are attached to each string are made of steel. Steel is much stronger than pure iron because it contains carbon, which makes it more flexible, and therefore less brittle. Because it has a small degree of flexibility, when we turn the pin with our tuning hammer, the pin actually twists a little. The problem is that if we tuned all the pins and walked away for a few hours, many of them would twist back. That means that half the battle is getting the piano in tune, and the other half of the battle is getting it to stay there. What tuners do to remedy this problem is to turn the pin a little farther than necessary, then turn it back the other direction. This way it is on pitch, but with no twist in the pin.

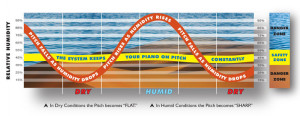

Many piano owners may have heard the term pitch raise. Raising the pitch of a piano means that it has gone so long without tuning that the strings are flat. Not just a little flat, but at least ten cents or more. Figure that a piano probably drops in pitch about five cents per year just from sitting. If a piano goes two years or longer without tuning, it’s probably time for a pitch raise. The reason a pitch raise is special is not because the tuner has to move his arm farther to tune each string. It has to do with the amount of tension on the plate which holds the strings. Consider that 230 strings, each with more than 100 lbs of tension, produce a combined load of about 30,000 lbs. Imagine if the tuner pulled each string and increased its tension by ten percent. That would effectively add 3,000 lbs of tension to the piano. This in turn causes the piano to shrink ever so slightly, which then lowers the tension of the strings. The net result is that the piano is now flat again. On average, when you increase the pitch of all the strings, the piano will drop by about twenty percent of the amount that it was raised. For example, if the piano was 100 cents flat to begin with and you tried to do a normal tuning to bring it up to pitch, in the end it would still be twenty cents flat.

Tuners can employ one of two techniques to compensate for this. One is called a “chip tuning”. This means doing one complete tuning on the piano to get it close to pitch, then tuning it again. The second technique involves calculating how much the piano needs to be raised, then tuning it twenty percent higher than necessary so that after it drops, it will be at the right pitch. If the piano is only two or three cents flat to begin with, the rebound effect is nominal and it is safe to do a normal tuning. If the piano is more than ten cents flat, the tuner needs to employ one of the special pitch raise techniques mentioned here. The good news is that once a piano is brought up to pitch, it should remain stable and not require another pitch raise the next time it is tuned.

Hopefully this will give piano owners a solid grasp of the methods involved in tuning a piano. It is also hoped that owners will find a greater appreciation for the amount of skill and training necessary to be a piano tuner. For information about getting your piano tuner, please visithttp://lapianotuning.com

David Mann

Member Piano Technicians Guild